How to learn Japanese

This is a no-nonsense post on how to learn Japanese.

In this post, I lay out a basic description of how I attained intermediate competency in the Japanese language with a focus on reading comprehension. I describe the fundamental tools and sources I used as well as the rationale behind the design of my study plan.

Many gaps are left to the reader. I do not link every single resource, explain how to set up your flashcard software, etc. Instead, my goal is to give you the fundamental context behind what I did and why I did it, which should equip you with the ability to design your own course of attack.

If your goals and background are similar to my own, then I suspect you will experience good results by sticking diligently to a study plan not too dissimilar to my own.

My qualifications

Instead of blindly taking my advice, you should first understand why I am qualified to give advice on learning Japanese.

- I started learning Japanese in March of 2019.

- I have studied continuously since starting, for a total duration of ~3 years so far.

- I began studying with very little preexisting knowledge, although (1) I was already familiar with ~20 kanji from a Chinese heritage background, (2) I benefited from cognates between Japanese and Cantonese, and (3) I was familiar with a scattering of vocabulary from many years of watching anime.

- Currently, I can read manga and books smoothly, with some variation depending on the difficulty. My reading speed is low, but my comprehension and speed are high enough that I find the experience actively enjoyable. I was also able to fansub a 90-minute science fiction movie with little challenge.

- I do not generally watch raw (unsubbed) content or converse verbally in Japanese, and my proficiency at doing either is relatively low.

- My study has been consistent, but low-intensity. I have studied almost every day; however, the amount I study in any given day can be quite low. During my entire period of study, my time was also engaged via gainful employment, activities with friends, a relationship, travel, study of other languages (Mandarin Chinese), etc., and often I did not have more than half an hour or so to spare in a day.

- I have not taken the JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test), although I have no difficulty with the reading comprehension questions at the highest level (JLPT N1). I will likely prepare to write this exam in half a year or so.

As such, the recommendations I will give are well suited for you if your goals and situation match well with my own:

- No formal background, but preexisting context via media consumption

- An interest in developing reading/writing ability over conversational/aural proficiency

- A busy schedule that means drastic lifestyle changes (e.g. studying 5+ hours per day) are infeasible

- Willingness to grind through daily study habits without skipping days or giving up

If your situation is different, then the optimal path will differ from my own. For example, in the most drastic case, if you are willing to move to Japan and live and work there, that is probably the most effective option. Alternatively, if you are willing to go down the “full immersion” route and spend many hours per day actively listening to Japanese audio and painfully struggling through native TV shows from day 1 at a rate of 5 hours per episode, that is also probably fairly effective, although obviously infeasible for some people, for example if you have children, a job and social life, schoolwork, etc. (You will see references online to a method called AJATT, or “All Japanese All The Time.” This is basically for people who are NEETs.)

Also, if your focus is on conversation or aural proficiency, the recommended course of study might be much different. I felt that I would get the most benefit out of reading comprehension, and so I focused on developing my ability to read Japanese at the cost of other abilities like speaking and listening. This was because I do not have any intention of living in Japan and because most anime has reasonably high-quality English subtitles available, so I anticipated I would benefit the most from being able to read novels, raw manga, web content, etc. Of course, I do have some comprehension of spoken Japanese, and I think it will not be difficult to improve quickly in that area before any planned visit to Japan.

I like to think that I was able to successfully design and implement a plan of study that was well-suited to my busy schedule and which allowed me to accomplish my desired goals in a time- and effort-efficient manner. Overall, I would say that I am very pleased with my results so far. I am sure many people have gotten much farther than I have in the timespan of 3 years. However, I suspect they also worked much harder than I did. On the other hand, many other people study for years and never reach this level of ability!

Basic outline

Here is a basic chronological description of how I learned Japanese.

- At all times, I used Anki, which is a software for flashcard management that implements a spaced repetition system. Spaced repetition is a highly efficient aid to memorization and scales to tens of thousands of flashcards. It should be assumed that when I talk about studying or memorizing something, it was done so with Anki.

- I spent 3 months memorizing associations between English words and 3,000 common Japanese kanji using the “Remembering the Kanji” system. This is a highly controversial system, and I will describe it further in a later section. While I was studying using the “Remembering the Kanji” method, I casually watched several YouTube videos describing basic Japanese grammar.

- I spent 9 months memorizing vocabulary and grammar from the はじめての日本語能力試験 単語 N5-N1 series. This is essentially series of ~10,000 sentences of increasing complexity, where each sentence contains one new grammar point or one new vocabulary word.

- Afterward, I started reading light novels and manga. I noted down and memorized new vocabulary as they occurred.

- At no point did I use “traditional” resources such as textbooks that one might find in a college classroom. All of this study was essentially conducted alone.

Essentially, I spent 1 year intensively grinding through hundreds of flashcards per day (typically on my commute to and from work), and then immediately dove into reading native Japanese content. My daily time commitment was probably around 2-3 hours per day for the first year, tapering down to 30 minutes maximum at the 1.5 year mark and 15 minutes maximum at the 2 year mark.

Notice that the structured study in the first year alone results in an incredible amount of progress. In that first year, I studied nearly 40 new flashcards per day, along with reviewing old flashcards (which typically involved studying 300+ previously seen flashcards). If you have any recollection of foreign language classes in school, I am almost certain you learned new vocabulary words at a rate 10% or lower than that of 40 words per calendar day (56 words per weekday).

I focused heavily on developing a vocabulary and grammatical base because I felt that it would be too frustrating to read complex written content otherwise. I really dislike the experience of looking up every other word; it breaks the flow of my concentration and overall makes me less motivated. As such, I suspected that if I frontloaded a huge amount of vocabulary, it would help me dive into and truly enjoy reading native material. Although I cannot observe the counterfactual, of course, I think that this basically worked out as planned.

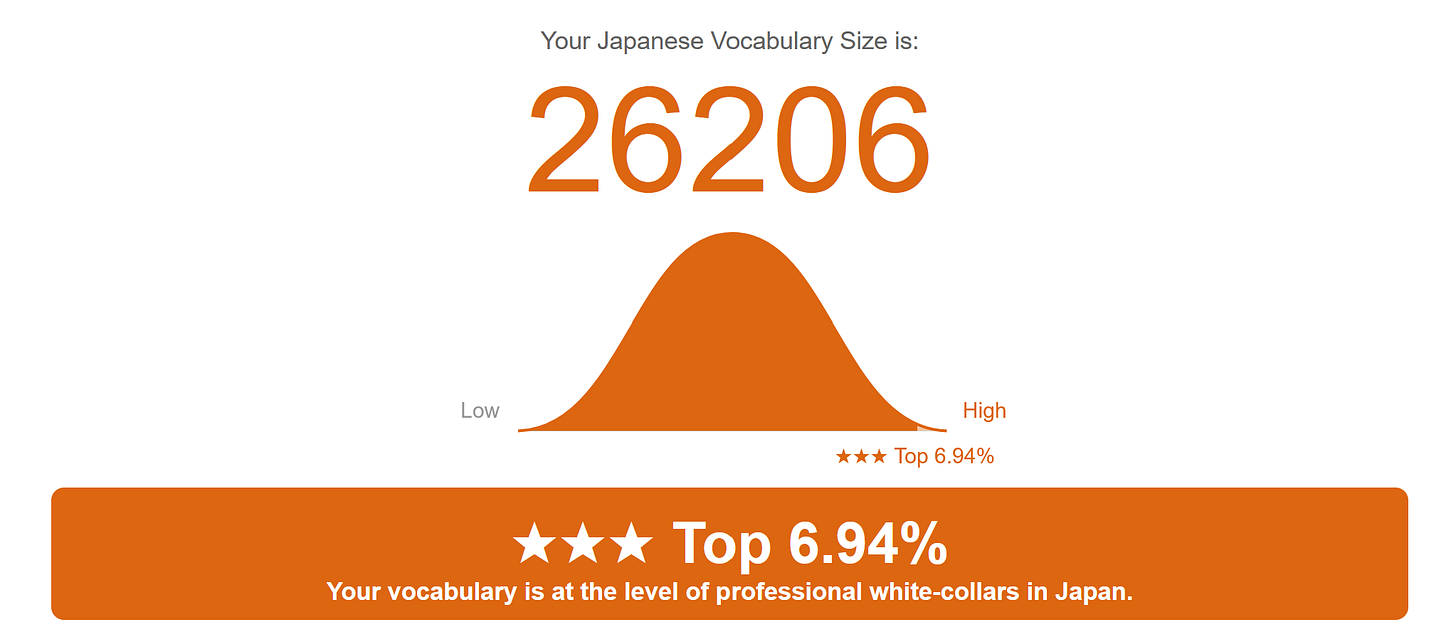

As a fun barometer, this online test purports to measure users’ knowledge of Japanese vocabulary. I just took this test, and I got this result:

Almost exactly a year ago, I scored 20,327 (top 23.54%, like an “18-year-old teenager”). I am pleased to see that my vocabulary has improved since then! If you search Twitter, you can find native Japanese speakers taking this test, who typically seem to report a score in the range of 29k-35k. In contrast, in this Reddit thread, only one user had a score higher than mine, and many people seemed to score well below 15k.

Obviously, this is not a perfect test, and just because you can answer a multiple-choice vocabulary question doesn’t mean you can understand the spoken word or use your vocabulary base effectively, and so on and so forth. However, it has at least some meaning, and you may find it gratifying to track your own progress with this test from time to time.

Spaced repetition

As previously mentioned, I use Anki, a flashcard-based spaced repetition system, to learn and memorize kanji, words, and grammatical concepts. It is worth describing what Anki is and why you should use it.

In general, the concept of spaced repetition is as follows. Suppose you want to memorize a new word. You can review this new word every single day, but that is obviously very time-inefficient. If you want to learn 10 new words per day, you end up accumulating an infinitely large study burden per day. However, in reality, we only need to see something relatively infrequently in order to remember it long-term. For example, if you review a new word on days 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, …, you may remember it just as well as if you studied it every day. This is called the principle of spaced repetition, where items to be memorized are reviewed with exponentially lengthening intervals between each review.

It is hard to describe how efficient spaced repetition is to those who have never tried it. Many people believe they have a “bad memory.” And, to be sure, there is definitely an innate component to how good you are at remembering things. Some people are simply luckier than others in the genetic lottery. However, the degree of individual genetic variation in memory ability simply pales in comparison to the boost you get from using spaced repetition. If there is a large corpus of information you want to memorize, you can remember it with <10% the effort and for >10x as long by using spaced repetition compared to someone who uses more “traditional” methods (brute-forcing a vocabulary list on random occasions and so on).

The tradeoff, of course, is that you have to be very disciplined with your study. For example, if the spaced repetition algorithm assigns you 300 flashcards for study each day, missing 1 day alone means that you are now behind and should study 600 flashcards the next day. If you miss that day as well, then now you have 900 to study, and so on. As such, if you are very aggressive with adding new flashcards, you must also be careful to not fall behind on your daily study. Naturally, once you stop adding new flashcards, the daily review burden slowly trails off over time.

Different implementations of spaced repetition algorithms exist. I use Anki, which is a very flexible software for creating and managing flashcard decks. It also supports online synchronization between desktop and mobile versions (both iOS and Android compatible apps exist). It works very well, which is good, because it’s basically the only option out there, aside from the extremely dated SuperMemo.

I generally think Anki’s default settings are quite reasonable. The only thing I change is setting the “New interval” in “Lapses” to 50%. This is actually very important. It means that if you mess up on a flashcard, you don’t immediately “lose all your progress” (so to speak). If you want to know more about this setting, you can Google it for a more detailed explanation.

Heisig’s “Remembering the Kanji”

I began my study with Heisig’s “Remembering the Kanji” (RtK). This is a highly controversial technique, and if you search on Google I am sure you will find countless arguments for or against it. I personally thought it was beneficial, but it requires you to grind through an unsatisfying couple of months without acquisition of any immediately applicable knowledge of Japanese. From the outside, RtK is actually very, very strange, but I want to give an argument for why it’s useful. Obviously, it’s possible to learn Japanese without using RtK, but that’s simply not what I decided to do.

Basically, the idea is this: James Heisig took 3k very commonly used kanji (first 2k described in RtK vol. 1 and last 1k described in RtK vol. 3) and paired each one up with an English word. For example, the kanji 女 might be paired with the English word “woman.” The kanji 女 itself is indeed a word meaning “woman,” and it may also be paired with other kanji to create compound words like 女王, “queen,” or 女生, “schoolgirl.” Hence in this case assigning the English word “woman” to the kanji 女 is fairly natural. In this case, what I did was I created an Anki flashcard with the word “woman” in English, and I marked the flashcard as correct only if I could draw the kanji 女 on my phone’s touchscreen.

For more complex kanji, the RtK system suggests that you memorize the word-to-kanji association by breaking them down into smaller components. For example, the kanji 優 is assigned the word “tenderness” in the RtK system. What you would do is to break it down into its components, namely the radical 亻 which is typically understood to be an abbreviated form of 人 (person, human, etc.) and the separate kanji 憂 which is assigned the word “melancholy” in the RtK system. To put the two components together, you can generate a mnemonic story of some sort to tie everything up, for example you might think of something like “a melancholy(憂) person(亻) should be treated with tenderness(優).”

You can kind of see that Heisig is structuring kanji as part of a directed acyclic graph with multiple roots, which you are traversing in what roughly resembles a breadth-first search. Each node is associated with both one Japanese kanji and a unique English word, and the task is to reproduce the kanji given the English word. I recommend reading the introduction of RtK vol. 1 for a more thorough description of this method.

On first sight, this is really a weird system! First of all, Japanese kanji are components of words, rather than words themselves. As such, no matter how many kanji you’re familiar with, you will never be able to put together or understand a Japanese sentence from that knowledge alone. Also, English words are obviously not perfectly mapped to Japanese kanji. For example, the kanji 仕 is assigned the word “attend” in RtK, but it is used in a large number of Japanese words with varying meanings such as 仕事 (“work”), 仕方 (“method”), 仕組み (“composition”). Various issues (easy to imagine) also arise from confusing similar English words, dealing with synonymous Japanese kanji, etc. Finally, as the kanji become increasingly complex, one has to come up with increasingly convoluted mnemonic stories to keep everything straight. One might therefore very reasonably ask what benefit there is to be expected at all from memorizing one man’s arbitrarily chosen associations between unique English words and Japanese kanji.

Here is my basic thought model for why RtK is beneficial, which draws upon the discussion in this paper as well as on my own experience. When you are beginning to learn Japanese, it is really difficult to remember all the kanji and keep them straight. In general, everything tends to look like a bunch of complicated lines thrown together without much reason, and people who don’t study through the RtK method report confusing pairs of similar-looking kanji, for example 右/左, 土/士, 末/未, 地/他, etc. Even beyond similar looking pairs, once you’re exposed to a sufficient diversity of vocab, things tend to look much like undifferentiated clusters of random lines, and people struggle greatly to retain vocabulary in such a setting.

I think part of why Japanese is difficult is because the vast dissimilarity to English (or other Western languages) means that it’s hard to get any “foothold” in the structure of the language. For example, one would ideally have a direct cognitive association between the kanji 女, the concept of “woman,” and multiple (5+) compound words formed using 女 as well as their pronunciations. Note that in general, individual kanji can be pronounced in multiple different ways depending on which compound words they show up in. Overall, this is a very complex network of associations, and penetrating it is very difficult, because the learner has no way to get a “foothold” in this complex abstract network of entirely foreign conceptual and linguistic associations.

For me, I felt that the benefit of RtK largely came from “seeding” this network of associations with a network of English words which map imprecisely to the true concepts that you’re trying to learn. For example, ideally when you see the kanji 仕 you should immediately think of compounds like 仕事 (“work”) or 仕業 (“deed/action”) in a conceptual way, with no English intermediary. You should also immediately associate it with the most common reading of the kanji, し (“shi”). What RtK teaches you is to instead first associate 仕 with the English word “attend.” As you subsequently learn vocabulary words like 仕事 and 仕業, you slowly replace all of the English-language associations of 仕 with a more pure, Japanese-language understanding. However, having that initial “seed” in your mental map of Japanese linguistic concepts helps a lot in that process. As a side result, I almost never confuse “similar-looking” kanji, which seems to be a common stumbling block for non-RtK learners.

After you do a bit of basic reading about the RtK method (vol. 1’s introduction and some online discussions), my basic recommendation would be to download a premade Anki flashcard deck of the kanji in RtK as well as PDF copies of vol. 1 and vol. 3 (ignore vol. 2 entirely), and then to go through at least the first 2k kanji worth of flashcards, training yourself to take as input the English keyword and produce the written kanji. It should take slightly under a month to study 1k kanji, so about 2.5 months for the entire batch of 3k. (For the impatient, though, the first 2k are much more valuable than the last 1k.) When I was about a year into learning Japanese, I stopped reviewing these flashcards entirely. By now, I have basically completely forgotten the English keyword associated with each kanji in the RtK corpus, and instead associate kanji with the Japanese compound words that make use of them.

In the three months that I was going through the RtK content, I also watched videos from the Cure Dolly YouTube channel on a frequent basis. Although I basically forgot most of the content immediately, it was still a useful “primer” for my memory and helped me get started on the next section of my study plan.

The bulk of my initial understanding of actual, functional Japanese was acquired by flashcarding ~10k sentences from the book series はじめての日本語能力試験 単語, which has one volume for each of the JLPT levels from N5 (easiest) to N1.

Grinding vocabulary and grammar

The easiest way to understand how this works is by imagining that you are trying to learn English as a foreign language. Suppose that I give you a series of sentences, each translated into your native language (be it Chinese, French, Japanese, whatever) in this hypothetical situation:

- Sentence 1: My name is Tom.

- Sentence 2: His name is Tom.

- Sentence 3: Her name is Mary.

- …

- Sentence 100: I will go to the store to buy an apple.

- Sentence 101: Tom will go to the store to buy a pencil.

- …

- Sentence 9,000: Today, I was really fed up with my coworkers’ teasing, so I quit my job and went drinking.

- Sentence 9,001: The economic situation in Poland is becoming increasingly unsettled due to new American tariffs on the price of imported potatoes.

- … and so on.

Clearly, these sentences are increasing in complexity. Specifically, each sentence is designed so that it contains one new element relative to all of the elements which have appeared in all the prior flashcards, where one “element” is either a new grammatical form or a new vocabulary word. Now suppose that you made a series of flashcards out of these sentences, testing your ability to take the English sentence and derive out the meaning in your native language, and studied 30-40 new flashcards a day. This is essentially what I did for Japanese.

This is incredibly effective. By studying these sentences, you become naturally drilled in the grammatical structure of Japanese sentences. In essence, you begin to acquire a basic intuition for Japanese grammatical structure at the same time that you’re memorizing thousands of vocabulary words.

You can find pre-made Anki decks for the content of these books here (as well as a great deal of other content): https://kitsunekko.net/. I also recommend searching online forums like Reddit for discussions of these books and the accompanying user-made Anki decks. They are usually referred to as “Tango N5” and so on. Contact me on Twitter if you have trouble finding Anki decks for this vocab, and I will send you the files myself (would honestly be surprised if more than 1-2 people ever did this).

There isn’t much else to say here. Yes, I am recommending that you sit down for 9 months and grind through ~10k flashcards to preload a huge amount of vocabulary, grammar, and intuition about Japanese sentence structure into your mind. You can of course pair this with reading basic native materials such as NHK Easy or light novels, but fundamentally the recommendation here is very simple. I literally loaded thousands of flash cards into my Anki deck and learned 40 of them every way, studying consistently on the commute to and from work. It is a very monotonous grind, at the end of the day!

Learning from native material

After studying for about a year from RtK and then from my はじめての日本語能力試験 単語 Anki sentence flashcard decks, I transitioned to reading a broad range of bilingual or native materials.

At this point, you may feel free to select readings according to your personal taste and inclination. Initially, I started off reading dual-language readers that let me check my understanding against an accompanying English translation:

- Japanese Stories for Language Learners: Bilingual Stories in Japanese and English

- Read Real Japanese Essays: Contemporary Writings by Popular Authors

- Read Real Japanese Fiction: Short Stories by Contemporary Writers

- Breaking into Japanese Literature: Seven Modern Classics in Parallel Text

After finishing these, I moved on to light novels, manga, and novels, such as:

- キノの旅 (Kino’s Journey)

- 人形の国 (Aposimz)

- こころ (Kokoro)

- … select whatever interests you here …

As I read, I take note of new vocabulary words that I haven’t seen before. (For example, a couple of words I just entered recently are: 告, 序盤, 没頭, 遇う, 取り繕う発破.) I would recommend creating a new Anki deck and making flashcards for these words. Personally, I have a Python script that takes in a plaintext list of Japanese words, pulls the English definition from Jisho.org, and outputs a .csv which I can import into Anki with just several clicks. I strongly recommend finding a method that works well for you.

One final thing I did was write scripts that downloaded entire categories of words from various sources and create small decks from the Jisho.org definitions. For example, I took a list of the 500 most common 4-character compounds (四字熟語) and memorized them, which is roughly analogous to studying a bunch of commonly used English idioms. This is super autistic, and I loved it, but your mileage may vary. Really anything goes at this point.

I plan to visit Japan at one point, and before I do so I will probably use services such as italki to hone my conversational abilities. Before then, though, I think I gain relatively little utility out of doing so, and relatively more enduring value out of simply consuming media that I really enjoy. So, for the time being, I have just been spending my free time reading books and manga.

My Anki stats

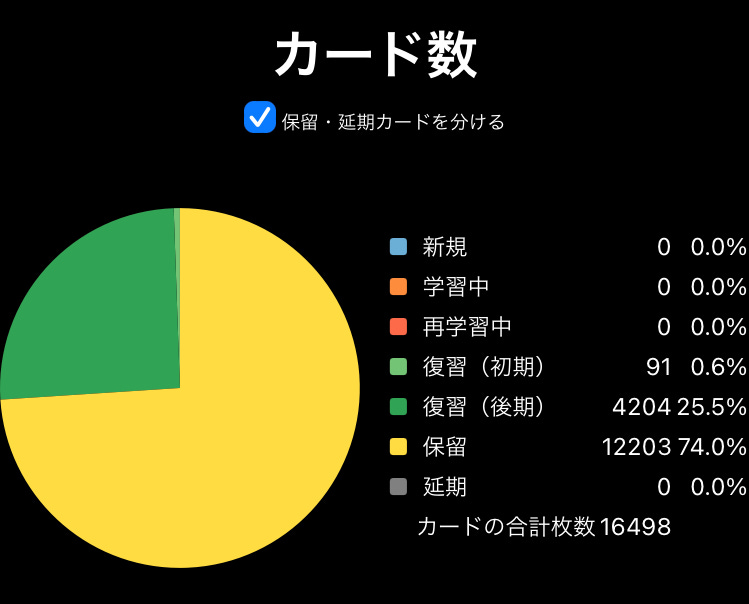

As a final note of inspiration, I would like to share some of my statistics from 3 years’ worth of Anki usage. These statistics apply only to my Japanese vocabulary flashcards, which excludes the ~3k kanji flashcards I used for RtK as well as ~10k flashcards I have for learning Mandarin Chinese.

My Japanese vocabulary deck is made up of about 16.5k words, ~10k of which are from the はじめての日本語能力試験 単語 series. The remaining ~6.5k words are ones I added myself, either after encountering them “in the wild” or by constructing custom sets of words based on my individual interests.

You may notice that 74% of these cards are suspended (yellow). As a time-saving measure, when the review interval goes beyond 1-2 years or so for any given flashcard, I suspend it. I expect that my natural consumption of Japanese media will expose me to any given word more frequently than once per year, and so it’s not necessary to keep them active in Anki.

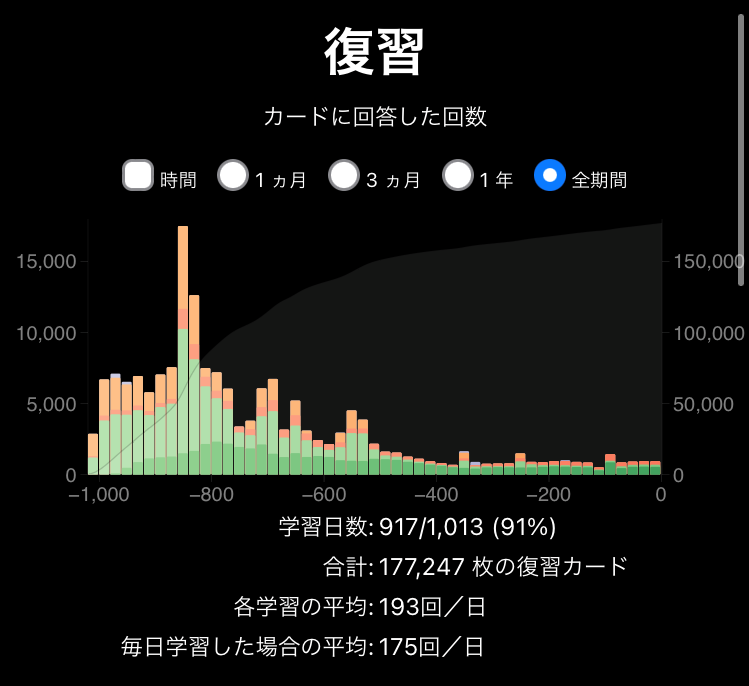

On average, I studied 193 flashcards repetitions per day. Obviously, the bulk of this is loaded into the first 1-2 years of study. The huge spike on the left hand of the graph represents 2019’s Christmas holidays, when I learned an enormous number of new flashcards per day. In total, I have performed over 177k flashcard reviews.

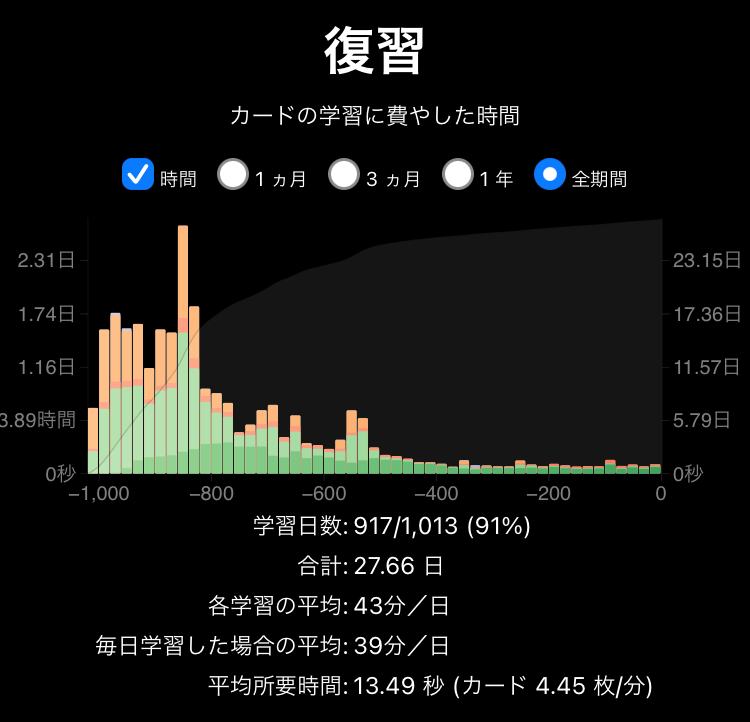

Finally, I’ve spent an average of 43 minutes per day learning and reviewing these flashcards, for a total of nearly 28 days’ worth of time. This is consistent with my estimate of a 2-3 hour daily commitment in the first year. Note that these numbers would probably be a lot lower if I studied in a more ‘concentrated’ way, rather than checking my messages or doing other things online after every 5 flashcards. So if you are a more efficient studier than I am, you may be able to accomplish the same amount in much less time!

Good luck!